On Whose Shoulders We Stand

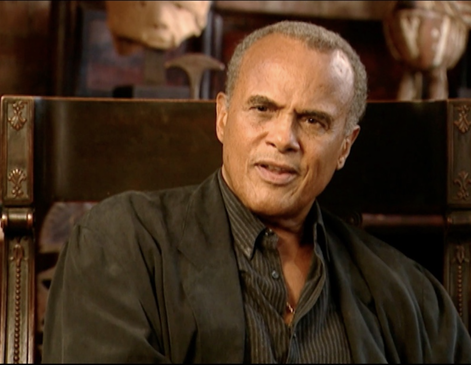

Screenshot from PBS “American Masters-Paul Robeson: Here I Stand” Interview directed by St. Clair Bourne, September 21, 1998

Screenshot from PBS “American Masters-Paul Robeson: Here I Stand” Interview directed by St. Clair Bourne, September 21, 1998 Harlem Writers Guild member

After having lived a robust ninety-six years, Harry Belafonte passed away five days ago. This news was a gut punch despite my not knowing him personally. I only saw him in person twice. Once, several years ago, as he walked onto the Apollo Theater stage. The other and more recent time was in his wheelchair at the Harry Belafonte 115th Street Library in west Harlem.

There was something about Harry Belafonte, especially in person. Grace. Power. Courage. Nobility. These are the words that come immediately to my mind. He is the archetype of manhood upon whose shoulders one can take flight toward personal growth and purposeful living. I feel the vacuum knowing he is now absent.

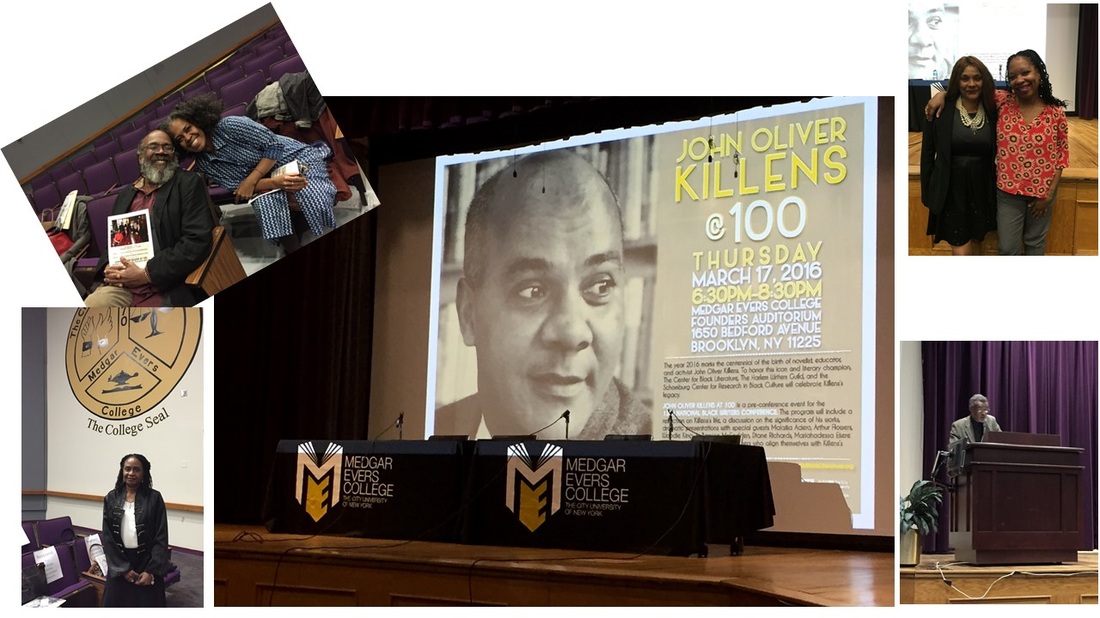

As a current member of the historic Harlem Writers Guild, of which Mr. Belafonte was a past member in the early 1950s, I wanted to understand the root of his inspired life more clearly. Of course, all the well-deserved tributes have and will continue to list his varied artistic and socio-political accomplishments as well they should. But why did he live life the way he did?

Artistically, he will forever be associated with his 1956 rendition of Day-O (The Banana Boat Song) from the album Harry Belafonte Calypso which popularized Caribbean music and culture in America as well as internationally. This one song fueled his commercial popularity and paved the way for his other artistic successes in music and film.

Have you really listened to the lyrics of Day-O? “Day-O! Day-O! Daylight come and me wan’ go home...Work all night on a drink of rum...Stack banana ‘til the mornin’ come...Come, Mister Tally Ma, tally me banana...Lift six foot, seven foot, eight foot bunch...Daylight come and me wan’ go home...” This is a plaintive, call-and-response work song summarizing the misery, backbreaking, and life-threatening labor endured from sundown to sunrise by Black men on banana plantations throughout the Caribbean (the so-called Banana Republics).

The indigenous populations of these various Caribbean countries considered the Banana Boat Song their anthem disparaging the exploitative business model and banana plantation system (the United Fruit Company) created in 1899 in Costa Rica by Americans Minor Cooper Keith and Andrew Preston (of the Boston Fruit Company) and which was sustained with the cooperation of the various Caribbean governments and the United States. The historical and sociopolitical context for these American businessmen is the 1896 US Supreme Court case ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson and the growth of racist Jim Crow laws.

In October 1928, almost two years after Harry Belafonte’s birth, thirty-two thousand banana plantation workers organized a strike against the United Fruit Company seeking real wages, better, and more safe working conditions. On December 5-6, 1928, it is estimated that three thousand men, women, and children who were protesting peacefully after attending Sunday mass in Ciénaga near Santa Maria, Colombia were machine-gunned down by the Colombian military (the Banana Massacre). These Colombian citizens were characterized as subversives, communists, socialists and a threat to the US, Colombia, and the United Fruit Company. The then US Ambassador to Colombia, Jefferson Caffery, sent the following dispatch to the US State Department- “I have the honor to report that the Bogota representative of the United Fruit Company told me yesterday that the total number of strikers killed by the Colombian military exceeded 1000.”

Eighteen years later, despite his honorable service in the US Navy during World War II, Harry Belafonte was faced with American racism at home. As a fledgling actor, along with Sidney Poitier and others at the American Negro Theater in Harlem, he had a fateful backstage meeting with Paul Robeson after performing in the theater’s adaptation of Sean O’Casey’s play Juno and the Paycock. From Mr. Robeson, Harry Belafonte learned about the richness and nobility of Black and African culture and the maxim that “...artists are the gatekeepers of truth.”

Harry Belafonte’s commitment to fight injustice was not a complement to his artistic talent and something he grew into after tiring of commercial artistic success. His social activism was not an afterthought. Rather the two were intertwined and inseparable. His lifelong association and friendship with Paul Robeson provided him the clarity and fortitude to live his life accordingly. The Banana Boat Song was not just a successful artistic commercial endeavor. It was Harry Belafonte’s initial expression of his mentor’s maxim, “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or slavery. I have made my choice. I had no alternative. The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people: despoiled of their lands, their true culture destroyed...denied equal protection of the law and deprived their rightful place in the respect of their fellows. –Paul Roberson” This is what was at the root of why Harry Belafonte lived life as he did.

While I feel the vacuum of Mr. Belafonte’s physical absence, I know his voice, his legacy of activism and integrity through the arts is embodied in the work of so many others and it persists. It is integral to the mission of the Harlem Writers Guild. And, as he stood on the shoulders of Paul Robeson, we now firmly stand on his.